Some 32,000 genes to go in squid research project

| WOODS HOLE, Massachusetts The room is filled with marine life: fiddler crabs and moon snails, dogfish and flounder. There are clams stacked up by the dozen, with signs that require second looks. "Toadfish infected with lice," one sign says. "Do not touch." But Joe DeGiorgis, 41, walks right past it all. He has come to the Marine Resource Center in Woods Hole for one thing and one thing only. "The squid are here," he calls out, pointing to a large oval tank. "My favorite guys." DeGiorgis, smiling, peers inside the tank. It's filled with dozens of long-finned Atlantic squid - 12 to 18 inches in length, or about 30 to 46 centimeters long, typical in every way as far as squid are concerned. DeGiorgis likes fried calamari as much as the next guy. But as a post-doctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health who spends half the year working at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, he has other reasons for admiring these mollusks. |

He and a colleague, J. Peter Burbach, a professor of molecular neuroscience at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, are the minds behind the Squid Genome Project, a surprisingly successful attempt to map the squid's genetic thumbprint in the hopes that its secrets may help solve mysteries like Alzheimer's disease.

On a budget of roughly $100,000, DeGiorgis and Burbach have identified more than 3,000 of the squid's estimated 35,000 genes, including, DeGiorgis said, the gene that causes the body to produce insulin, and genes linked to

Alzheimer's and a degenerative and fatal neurological disease called Niemann-Pick Type C in humans.

That's no small accomplishment. Stephen Sturley, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Columbia University, said DeGiorgis's work may one day help doctors find a cure for Niemann-Pick. And that, says DeGiorgis, is only the beginning.

"If the project were to stop today," he says, "I've got enough genes to work on for the rest of my career."

DeGiorgis grew up on Jacques Cousteau television shows and took up scuba diving in high school. He got his first job at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole before his senior year in college.

It wasn't much, just a diving job. DeGiorgis dove for surf clams in the sandbars off Martha's Vineyard and brought them back to Woods Hole for scientists to study. He came to learn that the scientists were interested in what marine life, namely clams and squid, could reveal about people.

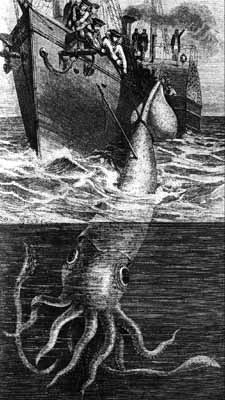

Squid, he learned, are especially powerful models. Their giant axon, a channel of nerve fibers in their back, is 1,000 times wider than the average human axon - an easy target for researchers who want to study how information travels and systems break down. DeGiorgis set up a private company to do dissections of the axon and other oddities. For a time in Woods Hole, he was the guy you called when you needed, say, 2,000 squid eyes, dissected and ready to be studied.

As DeGiorgis got his doctorate in cell and molecular biology from Brown University in 2001, he began to focus on mapping the squid genome.

"Some people were like: 'What would you do with it if you had it?' They didn't understand the significance of the work," he says. But DeGiorgis knew the squid could provide insight into the human condition.

DeGiorgis peers down at the squid in the water. He nets one, and it promptly sprays him in the face with black ink. DeGiorgis smiles.

Squid, he says, are beautiful.

source: IHT

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home